Washington-Dhaka trade pact risks Bangladesh’s sovereignty

- Update Time : Saturday, February 21, 2026

There are moments in a nation’s history when a signature becomes heavier than a speech, heavier even than an election. Bangladesh may have just experienced one. The so-called “reciprocal” trade agreement signed in the twilight of the interim administration was presented as a diplomatic triumph. Tariffs reduced — from 20 to 19 percent. Market access expanded. Strategic partnership deepened. The headlines were neat; the press releases are optimistic. But if one reads beyond the ceremonial language, the story shifts from celebration to concern.

This was not merely a trade deal. It was a strategic realignment disguised as commerce.

Let us begin with the arithmetic. In exchange for a one-percentage-point tariff reduction and preferential access for roughly 2,500 Bangladeshi products, Bangladesh has granted access to more than 4,400 American goods — including chemicals, medical devices, ICT products, automobiles, agricultural commodities, and energy supplies. Some tariffs are to be eliminated immediately; others phased out within five to ten years. On certain items, duties will be cut by 50 percent from day one.

That is not reciprocity in the classical sense. It is asymmetry, dressed up as a partnership.

More troubling are the embedded procurement “commitments.” Bangladesh has agreed, over 15 years, to purchase $15 billion worth of American LNG. It has signaled the acquisition of 14 Boeing aircraft for Biman Bangladesh Airlines. It has pledged at least $3.5 billion in agricultural imports, including wheat and soybeans. Military procurement from the United States is to increase, while purchases from “non-market economies” — an unmistakable reference to China and Russia — are to decrease.

This resembles managed trade, not free trade.

Critics have called it the weaponization of commerce. They are not wrong. Section 4.3 of the agreement allows the United States to reimpose punitive tariffs if Bangladesh enters into preferential arrangements with countries Washington considers “non-market.” Another clause requires Dhaka to adopt “complementary restrictive measures” if Washington imposes trade or security sanctions elsewhere. In effect, neutrality becomes contractually constrained.

For a country that has long balanced relations among global powers, this is not a small adjustment. It is a narrowing of strategic space.

The nuclear provision is even more restrictive. Bangladesh may not purchase reactors, fuel, or enriched uranium from countries deemed risky to U.S. interests — except under narrow exceptions. That condition casts a long shadow over future energy diversification. In an era where energy security determines industrial stability, pre-limiting supplier choice is not prudence; it is confinement.

And all this was signed by an interim government.

Here lies the deeper controversy. Major trade treaties shape defense procurement, digital governance, labor law, energy sourcing, and fiscal policy for decades. They are not administrative tidying-up exercises. They require parliamentary debate, public scrutiny, and electoral legitimacy. Yet this agreement was concluded days before a national election — binding the next elected government to obligations it did not negotiate.

Professor Muhammad Yunus and his administration may argue that they faced tariff pressure and acted pragmatically. But pragmatism without democratic mandate becomes overreach. Reducing a tariff by one percentage point hardly justifies locking in multi-billion-dollar strategic commitments.

The economic context makes the decision even more questionable. Government debt has surged 28% year-on-year to Tk 7.45 lakh crore in FY25. Net issuance of treasury bonds jumped more than 165%. Treasury bills expanded fourfold. The banking sector now holds nearly 69% of outstanding securities. Bangladesh is financing deficits amid sluggish revenue growth.

Under such fiscal strain, committing to large-scale aircraft purchases and long-term LNG contracts demands extraordinary caution. Will these procurements generate sufficient returns? Will they deepen debt exposure? Or will they crowd out alternative, potentially cheaper suppliers?

Economists have warned that the deal places more conditions on Bangladesh than in the United States. It has questioned whether modest tariff relief warrants such sweeping strategic concessions. It is right to raise that alarm.

Then there is the labor dimension. Restrictions on strikes are to be lifted; EPZs must be brought under general labor law within two years; penalties for anti-union discrimination must increase. Labor reform is not inherently negative. But when policy changes arise from external treaty obligations rather than domestic consensus, they risk backlash and instability. Reform must be owned, not imposed.

The digital provisions are equally consequential. Bangladesh must allow cross-border data flows and cannot impose customs duties on electronic transmissions. Customs transaction data must be screened and shared to identify “suspicious” trade. Export controls must align with US regulations. This expands American oversight over Bangladeshi trade flows. Sovereignty in the digital age is not abstract — it concerns data, surveillance, and control.

And yet, amid all this, one hears an argument whispered in Dhaka’s political corridors: There is no way out from a country like the United States. Better to align than resist.

That fatalism is dangerous.

History offers sobering lessons. During the Cold War, many states entered asymmetric arrangements believing patronage would guarantee stability. When strategic utility faded, so did protection. Even recently, a Pakistani defense minister remarked that America “dumps everyone after the job is done.” Whether one agrees entirely or not, the historical pattern of shifting alliances is undeniable.

To imagine that Bangladesh will be permanently shielded by favor is naïve.

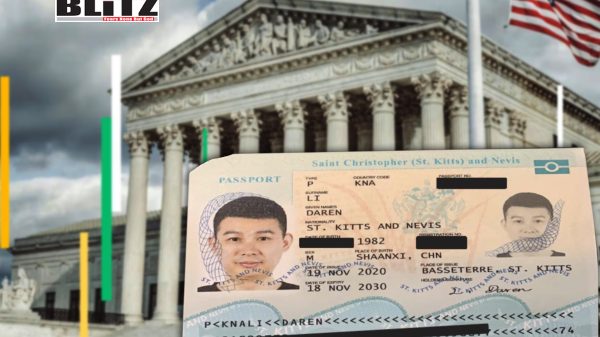

This brings us to the role of Khalilur Rahman, widely seen as instrumental in facilitating this agreement. If he indeed shepherded negotiations that embedded such sweeping commitments, he must answer a fundamental question: Was Bangladesh’s long-term autonomy adequately protected? Or was short-term diplomatic optics prioritized over structural balance?

Advisers come and go. Treaties endure.

Ultimately, however, the responsibility now shifts to the political leadership that will inherit this framework. Tarique Rahman, should he guide the next government, faces a stark choice. He cannot assume that patronage networks or personal channels in Washington will rescue Bangladesh from unfavorable clauses. Nor can he afford to treat the agreement as untouchable scripture.

Leadership requires clarity, not complacency.

He must conduct a transparent review. He must calculate the fiscal implications of LNG imports and aircraft purchases. He must assess defense procurement constraints and digital sovereignty risks. And if necessary, he must renegotiate aspects that compromise national interest. Diplomacy is not a one-time signature; it is a continuous process.

But renegotiation requires leverage. Bangladesh’s leverage lies in its strategic geography, its role in global supply chains, and its expanding consumer market. It is not powerless. It must act like it knows that.

Engagement with the United States is essential. No serious policymaker disputes that. America remains a central export destination and a technological leader. Yet engagement must not slide into dependency. Sovereignty is not measured by rhetoric but by retained choice.

Trade agreements should expand options. This one, in many respects, restricts them.

Professor Yunus’s government may have believed it was averting immediate tariff pain. In doing so, it may have imposed long-term constraints. Khalilur Rahman may have viewed the deal as strategic alignment. It may instead prove strategic narrowing. There is another school of thought that Yunus and khalil were instated for the purposes of the US. And it was a long time plan of US deep state to achieve the deal.

And if future leaders believe that loyalty will guarantee immunity, they should revisit the historical record. Great powers pursue interests, not sentiments.

Bangladesh must do the same. The ink is dry. The consequences are not.