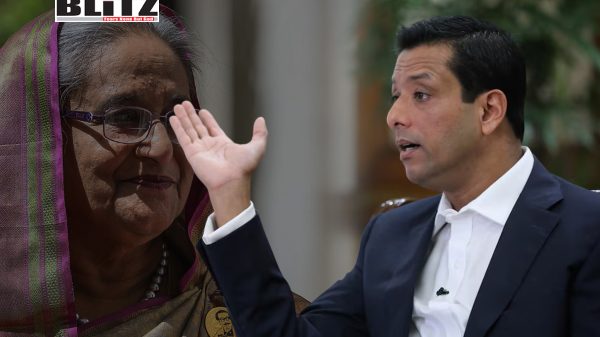

Sitting in the US, Sheikh Hasina’s son attempts to spoil Dhaka-Washington relations

- Update Time : Wednesday, February 4, 2026

There is something uniquely reckless about waging political war on your own country’s foreign relations while enjoying the protections of another’s. Sajeeb Wazed Joy has been doing exactly that. Sitting comfortably in the United States, the son of Bangladesh’s former prime minister has taken to public forums to smear Washington, insult its institutions, and poison a bilateral relationship that-after years of strain-is finally showing signs of repair.

It would be bad enough if this were merely bombast. It is worse because it is strategic vandalism.

Calling the Bangladesh Nationalist Party an “American puppet,” warning darkly of Jamaat-e-Islami’s looming takeover, alleging a “pre-determined” election outcome, and urging international condemnation of Bangladesh’s polls-these are not the words of a responsible political actor. They are the words of a man trying to internationalize his party’s domestic failures, even if it means burning bridges Dhaka needs to cross.

Start with the timing. US–Bangladesh relations are, quietly but unmistakably, improving. Military-to-military engagement has stabilized. Dialogue with major political parties has widened. Washington’s posture toward Dhaka has shifted from punitive suspicion to conditional engagement. This is not idealism; it is geopolitics. The Bay of Bengal matters. Bangladesh matters. And after a bruising period of mistrust, both sides appear willing to reset.

Enter Joy, stage left, with a flamethrower.

From American soil, he denounces American influence. He sneers at US diplomacy. He frames Bangladesh’s opposition as Washington’s marionettes. He insinuates that terrorists roam freely and elections are rigged beyond redemption. None of this helps Bangladesh’s credibility. None of it strengthens democratic norms. All of it invites external pressure and internal polarization.

Which raises an uncomfortable question: whose interests does he serve?

It certainly does not serve Bangladesh’s. Nor does it serve the Awami League’s long-term survival. What it does do is undermine US confidence at a moment when Washington is reassessing its South Asia strategy-and when Beijing is eager to fill any vacuum created by American disengagement. China does not need to persuade Washington to step back from Bangladesh if Bangladeshi elites are willing to do the job themselves.

Joy’s rhetoric reads like a gift-wrapped brief for those who argue that Bangladesh is unstable, unreliable, and unworthy of deeper partnership. That argument, once accepted in Washington, rarely benefits Dhaka. It benefits others-actors who prefer a Bangladesh insulated from Western scrutiny and embedded more deeply in illiberal spheres of influence.

The irony is thick. Joy warns of Jamaat’s influence while performing the very act that historically empowers fringe forces: delegitimizing electoral processes in advance and urging international isolation. He speaks of security while broadcasting instability. He claims to defend constitutional democracy while inviting foreign condemnation that weakens civilian institutions.

There is also the matter of credibility. Joy is not an impartial observer. He is a partisan actor whose own record shadows every word he speaks. The US administration’s seizure and forfeiture actions against assets linked to him were not symbolic gestures; they were legal determinations grounded in investigations. Those actions, widely reported, raised serious questions about corruption during his time in power. They punctured the moral authority he now claims when lecturing others about democracy and governance.

Corruption, after all, is not a footnote in Bangladesh’s political crisis. It is central to it. And when a figure associated-fairly or not-with illicit enrichment positions himself as the guardian of democratic virtue, the message collapses under its own weight.

Joy’s behavior is also politically unacumenal. The Awami League does not need an exiled surrogate antagonizing Washington. It needs to rebuild trust-at home and abroad-through restraint, reform, and realism. Instead, Joy’s interventions suggest a bunker mentality: if we cannot control the outcome, we will discredit the arena.

That strategy rarely ends well. Ask leaders who mistook international isolation for nationalist defiance. Ask parties that confused loudness with legitimacy.

The United States, for its part, should not be passive. Washington has laws precisely for this reason: to prevent its territory from being used as a platform for activities that undermine foreign relations or launder the reputations of individuals implicated in corruption. If Joy is, as records suggest, a convicted or legally sanctioned figure with confiscated assets, then the Trump administration-or any administration serious about accountability-should act accordingly.

This is not about silencing dissent. It is about enforcing standards. America cannot credibly promote good governance abroad while offering safe harbor to those accused of hollowing it out elsewhere. Nor can it tolerate the use of its freedoms to sabotage diplomatic relationships it is actively trying to repair.

Joy’s recent remarks about militants “openly roaming,” about mobs running Bangladesh, about elections being the “last chance” to stop catastrophe-these are not analyses. They are alarms pulled without evidence, broadcast to foreign audiences with predictable consequences. They harden attitudes in Washington, alarm partners in the region, and feed a narrative of Bangladesh as perpetually on the brink.

One need not be a BNP supporter to see the damage. One need only be a Bangladeshi who understands how fragile external confidence can be-and how costly its loss becomes.

Bangladesh has legitimate challenges. Electoral credibility matters. Extremism must be confronted. Political violence is unacceptable. These issues require sober engagement, not transatlantic grandstanding. They require institutions, not influencers.

Joy claims to fear instability. Yet instability is precisely what his interventions encourage. By casting elections as illegitimate before ballots are cast, by framing opposition as foreign puppets, by urging international condemnation, he reduces the incentives for compromise and raises the stakes for confrontation.

The result is a narrower path forward for everyone else.

There is a final, more personal tragedy here. Joy could have chosen restraint. He could have used his access to advocate quietly for reforms, to bridge misunderstandings, to lower the temperature. Instead, he chose the megaphone. He chose accusation over persuasion. He chose spectacle over statecraft.

Bangladesh will outlast him. US–Bangladesh relations, if handled with care, will recover. But the damage he inflicts now is real, and it will be paid by others-by diplomats trying to rebuild trust, by soldiers navigating partnerships, by citizens whose country is portrayed as a problem rather than a partner.

History is unkind to those who confuse personal vendettas with national interest. It is even harsher on those who pursue them from abroad.