Muizzu’s ‘Chagos’ gambit: A risky play in the Indian Ocean

- Update Time : Wednesday, February 4, 2026

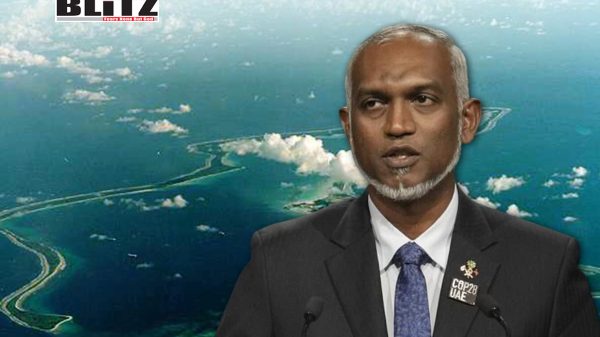

By any reasonable measure, the Indian Ocean has become one of the world’s most crowded strategic theatres. Sea lanes that carry the bulk of global energy supplies intersect with the ambitions of great powers and the anxieties of small island states. It is against this backdrop that Maldivian President Mohamed Muizzu’s recent comments on the Chagos Archipelago should be read—not as a casual diplomatic aside, but as a calculated and potentially dangerous move in a region where history, law, and power politics collide.

In an interview with Newsweek, Muizzu floated an extraordinary proposition: if the Chagos Islands were handed over to the Maldives, the United States could continue to operate its naval base at Diego Garcia. On the surface, it sounds pragmatic, even conciliatory. In reality, it is a proposal untethered from international law, dismissive of colonial history, and blind to the regional consequences—particularly for India and Mauritius.

The Chagos Archipelago has long been one of international politics’ unresolved moral debts. Detached from Mauritius by Britain in the 1960s, its inhabitants were forcibly removed to make way for a US military base. Decades later, the International Court of Justice and the United Nations General Assembly made their positions clear: Britain’s continued control of Chagos is unlawful, and sovereignty rightfully belongs to Mauritius. India, notably, has stood firmly behind this position, seeing it as part of a broader commitment to post-colonial justice and rule-based order in the Indian Ocean.

Muizzu’s proposal ignores this entire legal and historical edifice. The Maldives has no direct historical, legal, or moral claim to Chagos. None. To suggest that the archipelago could simply be “transferred” to Malé, with Washington’s strategic interests safeguarded in exchange, reduces a complex decolonization issue to a transactional bargain. It is diplomacy as deal-making, stripped of principle.

For New Delhi, the discomfort is obvious. India has invested years of quiet diplomacy backing Mauritius, not merely out of solidarity, but because Chagos represents a test case. If international law and UN resolutions can be brushed aside when inconvenient, what message does that send to smaller states that rely on these very norms for their survival? By inserting itself into this issue, the Maldives is effectively challenging a position India has defended consistently and publicly.

The irony is hard to miss. When the Maldives faced severe financial distress, India was among the first to respond—extending credit lines, restructuring debt, and ensuring essential supplies. This was not charity; it was neighborhood diplomacy rooted in stability and trust. Against that background, Muizzu’s comments strike many Indian analysts as not merely provocative, but ungrateful. Strategic autonomy is one thing. Strategic amnesia is another.

The United States angle makes the proposal even more curious. Diego Garcia is a linchpin of US military power, enabling operations across the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. But Washington does not need Maldivian mediation to secure its presence there. Even if Mauritius were to regain full control of Chagos, Port Louis could negotiate base access directly, under a framework consistent with international law. The idea that the Maldives could offer Washington a “better deal” than Mauritius is, at best, naïve.

So why float such a proposal at all? The answer likely lies in the Maldives’ evolving foreign policy under Muizzu. Since coming to power, his government has signaled a desire to recalibrate relations—dialing down India’s role while warming ties with China. The rhetoric around reducing Indian military presence, the softer treatment of the “India Out” narrative, and now this intervention in the Chagos issue all point in one direction: a deliberate attempt to reposition the Maldives as a more assertive, less India-aligned actor.

There is nothing inherently wrong with diversification. Small states often hedge to maximize leverage. The danger arises when hedging slips into adventurism. By stepping into the Chagos dispute, Muizzu is playing a game that involves far larger stakes than Maldivian domestic politics. He is inserting his country into a sovereignty dispute that touches Britain’s colonial legacy, America’s global military posture, India’s regional strategy, and Mauritius’s long-fought legal battle.

Mauritius, unsurprisingly, has reason to be uneasy. For decades, it has pursued the Chagos issue through courts and multilateral institutions, building a case grounded in law rather than power. External claims—especially from a country with no standing—risk muddying the waters and delaying implementation of favorable rulings. From Port Louis’ perspective, Malé’s comments are not just irrelevant; they are disruptive.

For India, the episode carries a broader lesson. The Indian Ocean is no longer a space where goodwill alone guarantees alignment. Economic assistance and diplomatic support, while necessary, are insufficient to anchor long-term partnerships. Regional politics are becoming more transactional, more opportunistic. Smaller states are testing boundaries, sometimes recklessly, to see what leverage they can extract from competing powers.

This does not mean India should respond with bluster or coercion. That would only validate fears of hegemonic behavior. But it does mean New Delhi must be clearer-eyed. Strategic patience should not become strategic complacency. India’s advocacy for international law in the Chagos case remains sound, but it must be accompanied by a firmer articulation of its red lines and interests in the region.

Muizzu’s gambit may yet fade into diplomatic footnotes. Or it may harden perceptions that the Maldives is willing to trade principle for short-term attention. Either way, the episode underscores a simple truth: in the Indian Ocean, geography may make neighbors inevitable, but trust is always conditional. When leaders forget history—and the help they received—they often discover that strategic games have longer memories than political sound bites.

As a military and international affairs analyst, one conclusion stands out. The Chagos controversy is not about islands alone. It is about whether the Indian Ocean will be governed by law or by deals. Muizzu’s proposal leans unmistakably toward the latter. And that is a gamble whose costs may far exceed any fleeting diplomatic visibility it brings.