Devastated Bangladesh trapped between two prodigal sons

- Update Time : Saturday, January 31, 2026

Bangladesh today resembles a house divided not by ideology but by inheritance. Its politics is no longer driven by arguments over policy or competing visions of the future; it is consumed instead by the unresolved ambitions of political heirs and the strategic miscalculations of those who still claim to be indispensable. The result is a republic caught between two prodigal sons—each emblematic of a deeper failure of judgment at the very top.

Consider first Tarique Rahman, the acting head of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP). Recently, Time magazine described him with a series of unflattering adjectives—hardly a novelty in international journalism. What was novel was Rahman’s decision to share the article himself on his verified social media pages. In a country where leaders routinely equate criticism with treason, this was a quietly subversive act. It signaled a certain awareness: that global scrutiny cannot be wished away, and that engaging with criticism is not necessarily a sign of weakness. In a political culture allergic to dissent, Rahman’s gesture hinted—only hinted—at a tolerance for free expression long missing from Bangladesh’s democratic practice.

Rahman has spent more than a decade and a half in exile, yet exile did not erase him. He survived court cases, factionalism, state pressure, and the slow erosion that often destroys parties cut off from power. The BNP remains one of the country’s largest political forces, and that endurance alone suggests a form of political instinct. Survival, after all, is a skill in South Asian politics. But survival is not the same as wisdom. And here lies Rahman’s looming test.

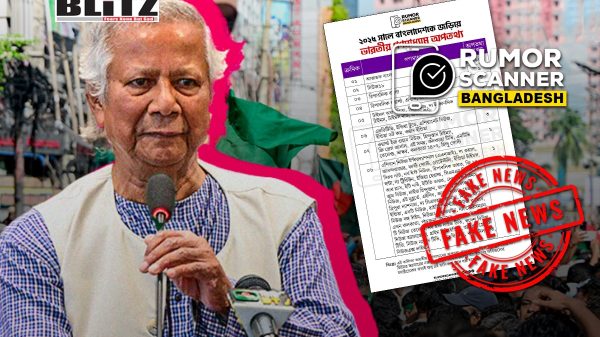

The interim regime led by Muhammad Yunus has declared that after the upcoming election, the newly elected parliament will function as a “constituent assembly” for 180 days. Translated from bureaucratic language into political reality, this means Yunus and his circle do not intend to relinquish power anytime soon. It is an arrangement that smacks less of democratic transition and more of ideological guardianship. One is reminded, uncomfortably, of Iran’s model, where elected institutions exist but ultimate authority rests elsewhere. Bangladesh is being prepared for a constitutional booby trap—one that future governments may find impossible to disarm.

Yunus has gone further, branding Bangladesh a “world champion of fraud.” It is a devastating accusation to level against one’s own country, especially from a figure elevated as a moral authority abroad. What is striking is not only the comment itself but the silence that followed. Tarique Rahman, Dr. Shafiqur Rahman said nothing. Sheikh Hasina said nothing. Nor did other major political figures. Had any of them made such a statement, the country’s intellectual class would have erupted in righteous outrage. The silence suggests either fear or calculation—or worse, resignation. It sends a grim message to ordinary citizens: that a managed election may be coming, but moral accountability will not.

Against this backdrop, rumors persist that Tarique Rahman is determined to contest the election at any cost. This would be a catastrophic error. There is a crucial distinction in politics between compromise and capitulation. The first can stabilize a nation; the second destroys careers. Rahman risks confusing the two. Pakistan offers a cautionary tale. Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif governs through accommodation with Army Chief Asim Munir. The result has not been stability but the consolidation of military dominance. Imran Khan sits in prison; civilian authority shrinks by the day. Sharif may yet discover that today’s compromise of politics becomes tomorrow’s political obituary.

If Rahman is one prodigal son, Sheikh Hasina faces her own dilemma with another. Her recent interview with the Associated Press—conducted via email, cautious to the point of sterility—contained one notable admission: that the 2014 and 2024 elections suffered from flaws due to BNP’s non-participation. This was less a revelation than a reluctant acknowledgment of the obvious. Otherwise, the interview recycled familiar talking points, suggesting a leader increasingly insulated from both criticism and consequence.

What Bangladesh needs from Hasina is not another mediated exchange but a direct address—unfiltered, unscripted, and honest. Instead, the spotlight shifted to her son, Sajeeb Wazed Joy, whose interview with Al Jazeera raised more questions than it answered. Joy’s remark that his mother would retire because she “is old” may sound unremarkable in a Western context. In South Asia, it was jarring. Age here is not merely biological; it is political capital, cultural authority, and moral legitimacy. Millions of Awami League activists see Sheikh Hasina not as a transient officeholder but as their final guardian.

Joy’s comment felt culturally tone-deaf and politically reckless. It exposed a distance—not just generational but civilizational—between leadership at home and heirs abroad. Had Sheikh Mujibur Rahman lived into old age, no one would have dared frame his leadership in terms of expiry. Joy’s remark placed him outside the emotional grammar of the party he is presumed to inherit.

Worse, it invited speculation about internal power struggles. Whether intentional or not, it handed Awami League’s rivals a narrative of decay and division.

Meanwhile, Tarique Rahman has shown signs—again, only signs—of political maturation. Exile has tempered him. From his late mother, Begum Khaleda Zia, he appears to have learned patience. Like Bilawal Bhutto or Rahul Gandhi, he has kept his party intact despite long absence. Charisma by inheritance is a fragile thing, but it can sustain an organization if handled carefully.

Yet both camps share a fatal weakness: an astonishing inability to manage the media. Sheikh Hasina’s recent interviews reveal poor preparation and strategic complacency. Tarique Rahman’s media operation, meanwhile, oscillates between lethargy and hubris, projecting him as a de facto prime minister without mandate or mechanism. In politics, perception precedes power. Projecting authority prematurely is an invitation to be neutralized.

The Awami League now stands at the edge of irrelevance. This is not hyperbole. Parties do not collapse only from electoral defeat; they collapse from succession crises and strategic delusion. This is no moment for Hasina to experiment with an untested heir. She must decide whether to revive her party or preside over its burial. History is unforgiving to leaders who confuse legacy with longevity.

If Time magazine sees Tarique Rahman as a prodigal son, Sajeeb Wazed Joy belongs uncomfortably in the same category. Bangladesh is trapped not between ideas but between heirs—each carrying the weight of lineage without yet proving the burden of leadership. Until that changes, the country’s devastation will not be an accident of history. It will be a choice.