Sino-Pakistan axis gradually pushing Bangladesh towards the destination of Iran

- Update Time : Wednesday, January 21, 2026

Bangladesh today stands on the edge of a transformation far more dangerous than many are willing to admit. What is unfolding is not a routine political transition, nor a democratic correction after years of flawed governance. It is the steady replacement of constitutional rule with revolutionary authority – a shift that carries grave consequences for Bangladesh itself, for India, and for regional stability across South Asia.

The violent removal of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in August 2024 marked more than the fall of a government. It marked the collapse of constitutional continuity. Whatever the failures of the Awami League, Hasina’s administration was elected, internationally recognized, and strategically aligned against Islamist extremism. Its downfall created a power vacuum that has since been filled not by elections, but by unelected authority.

Muhammad Yunus assumed power amid this chaos, not through popular mandate but through circumstance. What was initially described as a temporary, corrective arrangement is now being converted into something far more permanent. The proposed February 12 referendum lies at the heart of this transformation.

Marketed as an expression of “the people’s will”, the referendum is, in effect, a substitute for general elections. Its objective is not democratic renewal but political consolidation – granting Yunus extraordinary authority under the banner of revolutionary legitimacy. This is not an intangible concern. History shows that referendums held under transitional regimes rarely constrain power; they legitimize its concentration.

Bangladesh has been here before. Mass movements have repeatedly promised democratic rebirth, only to produce new forms of authoritarian control. What distinguishes the current moment is the explicit rejection of constitutional checks in favor of revolutionary justification. Courts, parliaments, and elections are portrayed as obstacles rather than safeguards.

The July 2024 unrest is now mythologized as a “people’s uprising”. That narrative, endlessly repeated, serves a purpose. Revolutions require symbols, martyrs, and slogans. But street mobilization, however genuine its grievances, does not grant unlimited governing authority. Crowds can topple governments. They cannot replace institutions.

As this internal shift unfolds, Bangladesh’s external orientation has changed with alarming speed. Engagement with China has intensified, particularly in infrastructure and defense-related sectors. Beijing’s involvement is no longer discreet.

For India, this should set off alarm bells. Bangladesh occupies a critical strategic position along India’s eastern flank and the Bay of Bengal. A Dhaka increasingly aligned with Beijing is not merely a diplomatic setback; it is a strategic recalibration with long-term consequences.

Pakistan’s role must also be acknowledged. As China’s closest regional partner, Islamabad has every incentive to encourage a weaker, ideologically pliable Bangladesh. Islamist networks, long nurtured by Pakistan’s spy agency Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI), thrive in environments where constitutional authority erodes. A Bangladesh drifting toward revolutionary governance creates precisely such conditions.

Western governments, meanwhile, appear trapped in cautious ambiguity. Diplomatic statements continue to emphasize “inclusive dialogue” and “peaceful transition”, yet there is striking silence on the central issue: the abandonment of elections in favor of a referendum designed to entrench power. Silence, in this context, is not neutrality. It is tacit consent.

The comparison with Iran is uncomfortable but unavoidable. We have seen how after 1979, revolutionary leaders in Iran argued that extraordinary circumstances required extraordinary authority. Elections were sidelined. Institutions were subordinated. A Supreme Leader emerged, justified by revolutionary necessity. The result was not liberation, but decades of brutal repression.

Bangladesh is not Iran. Its society is different, its history distinct. But the political logic now being deployed – revolutionary legitimacy over constitutional governance – follows a familiar and dangerous pattern. Once power is centralized in the name of revolution, it rarely disperses voluntarily.

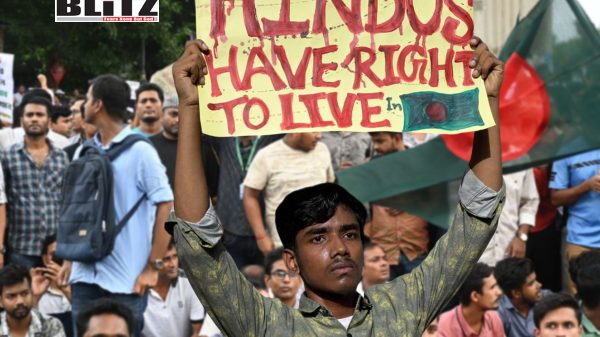

For ordinary Bangladeshis, the costs are already visible. Economic uncertainty persists. Political pluralism is shrinking. Opposition voices are marginalized or silenced. What was promised as a short transition is beginning to look like an open-ended experiment in rule without mandate.

Conceivably the clearest indicator of where Bangladesh is headed lies in what is now happening in plain sight. China’s ambassador in Dhaka, Yao Wen, has been publicly observed aligning himself with campaigns supporting Muhammad Yunus’s proposed referendum – an extraordinary departure from diplomatic convention and a signal of Beijing’s deep interest in the outcome.

Simultaneously, the Yunus administration has come under fire for deploying Indian-donated ambulances equipped with ICU facilities for referendum-related campaigning, a move widely seen as a calculated snub to New Delhi and a gesture of political deference toward China.

Yet even as these developments unfold, much of the Western diplomatic community appears content to look the other way. While attention remains nominally fixed on the February 12 general elections, the US envoy in Dhaka, Brent Christensen, continues meeting political figures under the banner of “working with all Bangladeshi political parties to advance shared peace and prosperity”. What remains conspicuously unaddressed is the administration’s overwhelming preoccupation with pushing the referendum – and its growing willingness to sideline elections altogether.

For India, the implications are profound. A destabilized Bangladesh aligned with China and Pakistan would alter the strategic balance in South Asia. It would complicate border security, embolden extremist networks, and undermine regional cooperation. This is not a distant possibility. It is a trajectory already taking shape.

The tragedy is that this outcome was not inevitable. It is the product of misjudgments – domestic complacency, foreign meddling, and a reckless belief that revolutions can be managed without consequences.

Bangladesh still has a choice. Elections can still be restored. Constitutional order can still be reaffirmed. But the window is narrowing rapidly.

History teaches a ruthless lesson: when leaders claim power in the name of “temporary necessity”, that necessity has a way of becoming permanent. If the February referendum proceeds as planned, Bangladesh may soon discover that what was lost in the name of revolution will not be easily recovered.

India, and the wider international community, should not wait until the damage is irreversible. By then, the cost of silence will be far higher than the cost of speaking now.