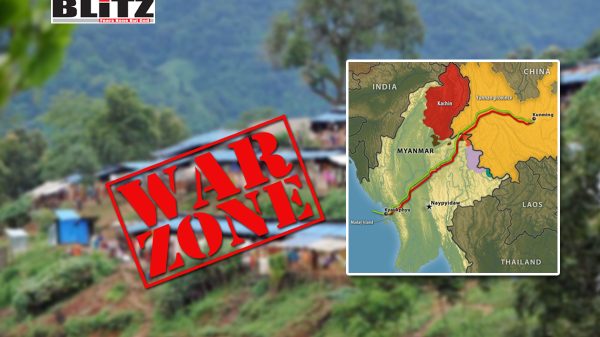

Myanmar Kachin state’s rare earths turns forgotten war zone into new fault line in US-China rivalry

- Update Time : Thursday, September 25, 2025

Most Americans would struggle to locate Myanmar on a map, let alone its northernmost state of Kachin. Yet this rugged, mountainous frontier—wedged between China and India—has once again emerged as a geopolitical flashpoint. For Washington’s strategists, it looks like an opportunity: a region where old alliances, mineral wealth, and Chinese vulnerabilities converge. For anyone with a sense of history, however, it is also a reminder of how the United States tends to wade into other people’s wars, misread local complexities, and leave behind wreckage more enduring than its promises.

The US has a history in Kachin, though it is one most Americans have long forgotten. During World War II, the Office of Strategic Services—the forerunner of the CIA—relied on Kachin fighters to harass Japanese forces in Burma’s jungles. These ragtag but resolute men, later dubbed the “Kachin Rangers,” guided inexperienced American pilots and soldiers through a terrain they could barely survive in without local help. Many Kachin families still tell stories of their grandparents fighting alongside young Americans who barely knew how to handle a machete, much less live in a tropical jungle.

That history explains why a surviving Kachin veteran could tell an interviewer decades later: “It is my duty to help because the Americans liberated us.” It is a bond born of circumstance and sentiment—but also a bond Washington has repeatedly exploited, from Cold War experiments arming Kuomintang remnants in Myanmar, to today’s subtle flirtations with the Kachin Independence Army (KIA).

Fast forward to October 2024. The KIA captured two key towns, Chipwi and Pangwa, both rich in rare earth elements. These minerals—vital for everything from smartphones to fighter jets—have become the oil of the 21st century. Beijing imports heavily from Myanmar, using the supply to buffer its own near-monopoly on global production. By February 2025, Chinese imports from Myanmar had plunged by nearly 90 percent.

For Washington, that is music to the ears. America has long fretted over its dependence on Chinese rare earths. What better than to see China’s own backyard supply routes threatened by an armed group with historical and cultural ties to the West?

Yet what seems like clever strategy risks becoming reckless overreach. Encouraging or covertly supporting armed movements to disrupt Chinese access to resources is the sort of short-term gain that historically produces long-term blowback. The CIA’s backing of Afghan mujahideen in the 1980s helped drive out the Soviets—only to empower extremists who later turned their weapons against the United States. Myanmar’s labyrinth of ethnic conflicts offers a similarly combustible mix.

China, for its part, is deeply unsettled. For years, Beijing relied on Myanmar’s generals as pliant partners, investing billions in pipelines and infrastructure to secure alternate routes for energy imports. Those pipelines were designed to mitigate China’s “Malacca dilemma”—the vulnerability of sea lanes patrolled by the US Navy.

But the junta’s grip is slipping. Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs), from the KIA in the north to others along the borders, now control large swathes of territory. Beijing’s client looks less like a stable partner and more like a sinking ship. The prospect of a Christian-led, West-friendly militia cutting off strategic minerals is exactly the kind of nightmare Beijing obsesses over.

It is also exactly the kind of temptation Washington finds irresistible: a chance to weaken China without deploying Marines or spending trillions. Hence the symbolism of US.= envoy Susan Stevenson’s visit to Kachin-held areas in August 2025. Officially, it was humanitarian. Unofficially, it was a signal.

Here is where American hubris intrudes. Washington too often sees foreign conflicts through a lens of opportunity rather than reality. It views Kachin fighters as plucky underdogs in a morality play against authoritarianism. It overlooks the fact that Myanmar’s ethnic conflicts are not neatly democratic struggles but overlapping feuds—ethnic, religious, tribal, and commercial—spanning seven decades.

The KIA is not a Jeffersonian militia yearning for liberal democracy. It is a battle-hardened force with its own hierarchy, revenue streams, and interests. Yes, its leaders are mostly Christian in a Buddhist-majority nation, with Baptist roots dating back to 19th-century American missionaries. But that cultural affinity hardly translates into alignment with US. goals. Washington should know better than to conflate religious familiarity with political reliability.

The American record here is abysmal. In Vietnam, the US mistook Catholic elites as natural allies against communism, ignoring the nationalist undercurrents driving the conflict. In Iraq, Washington assumed Shiite exiles would build democracy after Saddam Hussein’s fall, only to unleash sectarian carnage. In Afghanistan, Pashtun warlords were treated as partners in governance, even as they undermined the very state America sought to construct.

Why would Myanmar be any different?

Washington’s growing fascination with Kachin risks not just repeating mistakes but escalating great-power confrontation. For Beijing, Myanmar is not just another neighbor; it is a corridor vital to its energy security. If the US is perceived as deliberately undermining that corridor, it raises the stakes of US-China competition in ways that could spiral beyond control.

The Kachin themselves risk being used as pawns in this rivalry. America’s flirtation offers them recognition and perhaps some support. But history suggests it will not last. When Washington’s priorities shift—as they inevitably do—the Kachin may find themselves abandoned, as so many other US-backed groups have been. The Kurds in Syria and Iraq know this story all too well.

Myanmar’s Kachin crisis is not just a regional conflict. It is a mirror reflecting the broader dynamics of 21st-century power politics. America should remember that it has been here before, in the same mountains no less, and its interventions sowed instability that still lingers. The Kuomintang remnants armed by the CIA in the 1950s morphed into actors in the drug trade and destabilized borderlands for decades. Do we really want to run that experiment again under the banner of rare earths?

Consider also Egypt in 2011, Libya in 2012, Syria in 2013: moments when Washington thought it could tilt fragile conflicts toward freedom, only to leave chaos in its wake. Or the more recent case of Afghanistan, where two decades of blood and treasure ended with the Taliban flying American helicopters in victory.

None of this absolves China. Beijing has long treated Myanmar as a client state, exploiting its resources and shielding its generals from accountability. Its alarm over Kachin resistance is not rooted in concern for Myanmar’s democracy but in the safety of its pipelines and mines.

But America should resist the urge to play spoiler simply because China is unsettled. Great powers are not strengthened by opportunism in fragile states; they are weakened by the moral and strategic quagmires that follow. If Washington truly wishes to compete with China, it should do so through the strength of its economy, the attraction of its institutions, and the consistency of its alliances—not through another entanglement in a civil war half a world away.

The Kachin story, at first glance, seems tailor-made for America’s strategic imagination: brave fighters, critical minerals, Chinese vulnerabilities. But beneath that surface lies the reality of Myanmar’s fractured politics, America’s poor record of intervention, and the risk of drawing the world’s two largest powers into confrontation in one of Asia’s most unstable regions.

The mirage of “people power” once led Washington astray in Cairo, Kabul, and Baghdad. In Kachin, the mirage now wears the mask of strategic advantage. The United States should see it for what it is: another temptation to overreach, another trap that promises influence but delivers instability. In geopolitics, as in life, not every opportunity is worth seizing. Myanmar’s Kachin State is one of them.