Why Rohingya repatriation keeps failing and what must change

- Update Time : Monday, September 22, 2025

For nearly eight years, the Rohingya crisis has remained one of the world’s most intractable humanitarian tragedies. Close to one million Rohingya refugees continue to live in limbo inside the crowded camps of Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar district, unable to return to their ancestral homes in Myanmar’s Rakhine State. Forced out in 2017 during what the United States and the United Nations have both described as genocide, the Rohingya face dwindling humanitarian aid, deteriorating camp conditions, and the crushing despair of statelessness.

Despite repeated promises by governments and international institutions to facilitate their safe repatriation, every initiative has ended in failure. Buses have been lined up, agreements signed, and pilot schemes announced, but the refugees themselves have refused to board. The reason is simple: they do not believe they will be safe if they go back – and, judging by the situation inside Myanmar, they are right.

The question is no longer whether repatriation attempts have failed – the record is clear. The pressing question now is why they keep failing, and what must be done differently to prevent the Rohingya from becoming yet another permanently exiled population.

The most glaring flaw in past repatriation attempts lies in their design. From the beginning, negotiations have been conducted almost exclusively between Dhaka and Myanmar’s military junta. This approach ignored three essential realities on the ground.

First, the junta, while officially in control of Myanmar’s government, lacks legitimacy and does not hold effective authority in much of Rakhine State. Over the past few years, the Arakan Army – an ethnic Rakhine armed group – has seized control of more than half of Rakhine’s townships. Any repatriation plan that excludes the Arakan Army is detached from political reality and doomed to failure.

Second, Myanmar’s National Unity Government (NUG), the civilian opposition formed after the 2021 coup, has been excluded from these talks. While the NUG lacks military strength, it represents the democratic aspirations of millions of Myanmar’s citizens and has made gestures toward federalism and minority inclusion. Its recognition of the Rohingya, if formalized, could be pivotal for ensuring their citizenship rights in a future democratic Myanmar. Excluding the NUG means missing an opportunity to embed Rohingya rights into a broader political settlement.

Third – and most damaging – the Rohingya themselves have been sidelined. Refugee leaders have never been invited to the negotiating table. Their demands are clear: recognition of their ethnic identity, restoration of full citizenship rights, freedom of movement, and protection from persecution. Yet none of these conditions have been guaranteed by the junta, the Arakan Army, or even regional mediators. Asking refugees to return without assurances of dignity and security is not a genuine solution but an invitation to disaster.

Bangladesh has shouldered an immense burden since 2017, hosting close to one million refugees despite its limited resources and crowded population. Dhaka understandably wants to reduce the strain on its economy and the social tensions in Cox’s Bazar, where local resentment toward the refugee population has been growing. This has led Bangladesh to push for rapid returns, sometimes prioritizing speed over substance.

But this strategy has backfired. Each failed attempt has further eroded trust among the Rohingya, who now fear that their safety is being sacrificed for political convenience. Instead of creating momentum, the repeated breakdowns have entrenched suspicion and deepened the refugees’ determination not to return without ironclad guarantees.

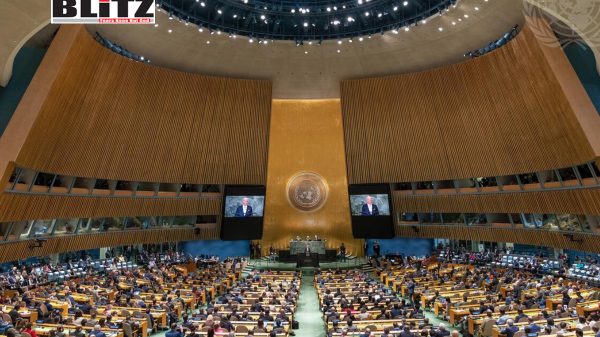

The international community has also failed the Rohingya in both political will and action. In 2022, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken officially recognized that Myanmar’s military had committed genocide against the Rohingya. Yet beyond rhetorical gestures and limited sanctions, Western engagement has been minimal. The United Nations, for its part, has largely confined itself to humanitarian operations, avoiding the tougher political questions.

Meanwhile, China has expanded its influence in Rakhine State through major infrastructure projects, including the Kyaukphyu port, but has shown no interest in securing justice for the Rohingya. Beijing’s priority is stability for its investments, not human rights. As a result, the global response has been fragmented, half-hearted, and ultimately ineffective.

The consequences of this stalemate are grave. Camps in Bangladesh are evolving into permanent settlements, aid flows are shrinking, and an entire generation of Rohingya youth is growing up without access to education or meaningful opportunities. The risks are not just humanitarian but strategic. Prolonged despair and hopelessness can drive radicalization, fuel human trafficking networks, and destabilize the wider region. What is unfolding in Cox’s Bazar is not just a refugee crisis but a ticking time bomb with regional security implications.

Breaking this cycle requires a fundamental rethink of the entire repatriation process. Three steps are critical.

- Involve the right interlocutors. Future negotiations must include the Arakan Army, which holds de facto authority in large parts of Rakhine, and the National Unity Government, which represents Myanmar’s democratic aspirations. Most importantly, the Rohingya themselves must have a seat at the table. Their voices, experiences, and demands must shape the conditions of return, otherwise they will never trust the process.

- Anchor repatriation in rights and security. Citizenship for the Rohingya cannot be treated as a bargaining chip. It is the foundation of any durable solution. Without legal recognition, freedom of movement, and reliable security guarantees, repatriation will not be sustainable. International donors should make clear that future assistance to Myanmar’s political actors – whether the junta, the Arakan Army, or the NUG – will depend on concrete commitments to Rohingya rights.

- Ensure regional and international buy-in. Bangladesh cannot carry this burden indefinitely. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), despite its reputation for inaction, must be pressed to take a more active role. The Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) should step up with financial and diplomatic backing. China, with its deep economic ties in Rakhine, must also be challenged to ensure its projects do not further entrench Rohingya dispossession.

The stakes are enormous. If the world continues along its current trajectory, the Rohingya could become another permanently displaced population, like the Palestinians, condemned to generations of exile and statelessness. Their culture and identity risk erosion inside the camps, while international attention gradually fades.

Yet repatriation remains possible – if the process is fundamentally reimagined. Negotiating solely with Myanmar’s junta while excluding both the real power brokers in Rakhine and the Rohingya themselves is a recipe for repeated failure. The world must abandon old formulas that have failed time and again.

The last eight years have taught one undeniable lesson: there can be no solution for the Rohingya without the Rohingya. Until their rights are guaranteed, their voices heard, and their future secured, the buses lined up in Cox’s Bazar will remain empty – and an entire people will remain exiled from their homeland.