South Africa pushes for trade breakthroughs in Washington amid tariff strains

- Update Time : Sunday, September 21, 2025

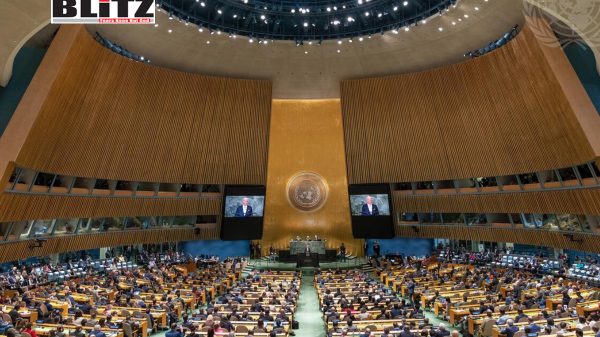

South Africa’s Trade, Industry, and Competition Minister Parks Tau has described his recent trip to Washington as “constructive,” despite the growing trade friction with the United States under President Donald Trump’s second term. His remarks followed meetings with US Trade Representative Ambassador Jamieson Greer, held just days before the 80th United Nations General Assembly (UNGA 80) convenes in New York on September 23.

Tau was joined by Minister of International Relations and Cooperation Ronald Lamola, both dispatched to Washington as part of Pretoria’s strategy to reset trade relations and soften the blow of new tariffs imposed on South African exports. In early August, the Trump administration slapped 30% tariffs on a range of South African goods, escalating tensions between the two countries and raising questions over the future of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), the preferential trade framework that has long underpinned bilateral commerce.

On X (formerly Twitter), Tau struck an optimistic note: “We held constructive talks with Ambassador Greer on our way forward on SA-US trade relations. Our teams have been in intense negotiations, and I will be briefing President Cyril Ramaphosa on the outcomes in due course.” His comments aimed to project confidence, but the reality of South Africa’s challenge is stark: persuading a protectionist White House to consider Pretoria’s proposals amid Trump’s broader push for reshoring and tariff-driven leverage.

The United States remains a top trade partner for South Africa. According to government data, South African exports to the US were valued at $8.2 billion (around R142 billion) in the most recent year. More than 600 US companies operate in South Africa, employing thousands and engaging in industries from energy to retail. Conversely, 22 South African companies maintain a footprint in the US, with investments ranging from mining and metals recycling to specialized manufacturing.

The relationship, however, is increasingly transactional. South Africa has benefited from AGOA, which provides duty-free access for thousands of products, but Trump has threatened to revisit or withdraw preferences for countries that he argues benefit disproportionately. Pretoria fears that unless a compromise is found, its exports-particularly in steel, automobiles, and agricultural produce-could lose their competitive edge in the US market.

In an effort to de-escalate tensions, the South African government has tabled a package of trade concessions designed to appease Washington while also safeguarding domestic industries.

One of the most significant offers is a ten-year plan to import large volumes of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the United States, which Pretoria says could unlock $12 billion in new US investments. This proposal aligns with Washington’s push to expand LNG exports and reduce reliance on other global energy buyers.

South Africa has also suggested simplifying US poultry exports under the 2016 tariff rate quota, potentially generating $91 million in trade for American producers. Poultry has long been a contentious point in bilateral relations, with US industry groups lobbying heavily for greater access to the South African market.

Additionally, Pretoria has proposed opening its market to US blueberries, a relatively new export crop with growing demand worldwide. These agricultural concessions are designed to sweeten the deal and demonstrate South Africa’s willingness to be flexible.

On the investment front, South African companies have committed to channeling $3.3 billion into US industries, including mining and metals recycling. Both governments are also exploring joint investments in critical minerals, pharmaceuticals, and agri-machinery-sectors considered vital for both economic diversification and supply chain security.

Importantly, Pretoria has stressed that certain sectors should be shielded from reciprocal tariffs. Exemptions are being sought for shipbuilding, counter-seasonal agriculture, and exports by small companies under $1 million annually, with officials warning that blanket tariff escalation would disrupt fragile supply chains and harm small- and medium-sized enterprises.

Despite the scale of South Africa’s offers, the Trump administration has so far shown little interest. According to officials, President Trump has “snubbed” the proposed deal, sticking to his hardline stance that tariffs are necessary to protect American jobs and industries. For Pretoria, this rejection underscores the difficulty of negotiating with a White House that values short-term wins over long-term trade partnerships.

Trump’s political calculus is also at play. With his administration framing trade as a zero-sum contest, concessions to South Africa-no matter how logical from a supply chain perspective-could be portrayed by domestic critics as weakness. Moreover, South Africa’s strong diplomatic ties with countries like China and Russia complicate the optics of any major deal in Washington.

Tau and Lamola’s Washington mission is not just about economics-it is also about politics. President Cyril Ramaphosa faces mounting pressure at home to shield South African industries from damaging tariffs while also keeping critical access to the US market open.

The South African Embassy in Washington has reinforced Tau’s narrative, declaring that the minister “reaffirmed South Africa’s commitment to expanding trade and investment cooperation with the US.” But whether goodwill statements can translate into policy change remains uncertain.

For now, Pretoria is balancing optimism with realism. The offers on LNG, poultry, blueberries, and reciprocal investments signal a willingness to compromise, but without reciprocal movement from Washington, the risk of prolonged stalemate looms large.

The timing of these talks, just before the 80th UN General Assembly, adds another layer of complexity. As world leaders gather in New York, Ramaphosa will be expected to project confidence in South Africa’s ability to protect its trade interests while also navigating the geopolitical rifts between the US and its global rivals.

If Washington maintains its tariff-first posture, South Africa may be forced to look elsewhere for growth-whether in deepening ties with the BRICS bloc, diversifying toward Asian markets, or pushing for greater intra-African trade under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). But losing ground in the US market would be a major blow, particularly for industries like automotive manufacturing, which rely heavily on American demand.

For now, Tau’s “constructive” framing reflects a diplomatic balancing act: projecting optimism to reassure domestic audiences, while quietly acknowledging that the road ahead is fraught with political and economic hurdles. Unless Trump softens his position, South Africa’s offers may remain on the table-unanswered, but symbolizing Pretoria’s determination to preserve a fragile yet vital partnership.