Europe embraces Modi as trade interests eclipse past human rights concerns

- Update Time : Monday, July 28, 2025

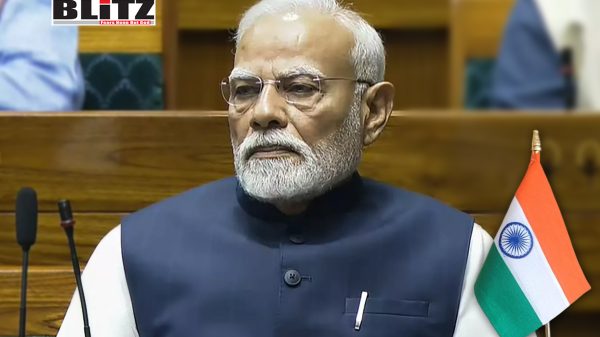

Just a decade ago, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was a figure of global controversy. His role in the 2002 Gujarat riots, during his time as chief minister, made him a political pariah in several Western capitals. Some European nations and even the United States denied him a visa. But times have changed dramatically. Today, Modi is being warmly welcomed across Europe and the broader West – not for his political transformation, but because of the irresistible economic and strategic pull of India.

This reversal was recently highlighted during Modi’s high-profile state visit to the United Kingdom. There, he received a grand reception, including a meeting with King Charles, and sealed a major trade agreement with newly elected Prime Minister Keir Starmer. The deal, touted as a landmark step in UK-India relations, aims to boost bilateral trade, which was valued at approximately £41 billion ($55 billion) in the year leading up to September 2024.

At the heart of Europe’s new embrace of Modi is not ideology, but commerce. India’s economy is growing rapidly. According to Morgan Stanley, the country is on track to become the world’s third-largest economy by surpassing Japan and Germany in the coming years. Its middle class, projected to reach 95 million by 2035, offers an enormous consumer base – larger than the population of any single European Union (EU) country. Western nations, struggling with stagnation and looking to reduce reliance on China, increasingly see India as an alternative economic partner.

In addition to its economic weight, India is also seen as a strategic ally. While it was once closely aligned with the Soviet Union during the Cold War, today India is viewed in the West as a key partner in maintaining a rules-based international order. Maritime security is one area of growing cooperation, especially in the Indian Ocean where nearly 40 percent of EU-India trade passes.

Although the United States is also exploring deeper trade ties with India, it is Europe that has taken the most concrete steps. In March 2024, the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) – composed of Norway, Switzerland, Iceland, and Liechtenstein – finalized a trade deal with India after 16 years of negotiations. The agreement includes €95 billion ($111 billion) in projected investments in Indian industries such as pharmaceuticals and machinery, and will result in India lifting tariffs on various imported goods.

The UK, for its part, has worked hard to secure its own deal with New Delhi. Post-Brexit Britain has sought new global partners, and India, with its historical and Commonwealth ties, has been a top target. The UK-India trade agreement promises to enhance British access to defense manufacturing, fintech investment through London’s financial sector, and collaboration in technology and telecoms.

Now, the EU is preparing for its turn. Earlier this year, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and the full College of Commissioners traveled to India – an exceptionally rare diplomatic gesture. The purpose was clear: to accelerate EU-India negotiations for a comprehensive trade agreement. The EU is already India’s largest single trading partner, with bilateral goods trade reaching €124 billion in 2023, nearly double the figure from a decade ago. Over 6,000 European companies operate in India, employing roughly 1.7 million people.

The proposed EU-India deal seeks not only to remove trade barriers but to enhance cooperation in digital infrastructure, green technology, and resilient supply chains – all key priorities for both sides. For the EU, aligning with India also serves as a hedge against global instability, particularly with worsening tensions between China and the West.

But this strategic and economic enthusiasm has come at a cost: a noticeable silence on human rights. Where once Modi’s government faced regular criticism for its treatment of religious minorities, press freedoms, and civil liberties, these issues now take a backseat to trade. Human rights organizations have accused Western leaders of abandoning their values in pursuit of economic opportunity.

Modi’s global reputation has undeniably improved. In 2023, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese even likened him to Bruce Springsteen, calling him “the Boss” during a public event in Sydney. Such comparisons would have been unthinkable a decade ago, when Modi was widely shunned by Western leaders.

Still, his diplomatic balancing act continues to draw criticism. Modi has refused to condemn Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, maintaining close ties with Moscow and purchasing large volumes of discounted Russian oil – much of which used to go to Europe. Russia also remains one of India’s largest arms suppliers. This has raised eyebrows in Brussels and Washington, but has not derailed trade talks.

In fact, Modi’s position on Russia is seen by many in Europe as part of India’s historical non-alignment policy – one that seeks to keep its options open. For European leaders desperate for new markets and more resilient supply chains, such diplomatic ambiguity is tolerated in favor of broader economic and geopolitical goals.

The momentum behind India’s global partnerships shows no signs of slowing. With deals already inked with EFTA and the UK, and EU negotiations well underway, New Delhi finds itself in a strong bargaining position. Modi, once sidelined, now stands at the center of Western diplomatic and economic attention.

In the end, Europe’s embrace of Modi reveals a deeper truth about international politics today: economic interest trumps moral posturing. The West, facing slowing growth, inflationary pressures, and rising global competition, increasingly views India not through the lens of its internal politics, but as a vital engine of future prosperity and strategic alignment.

Modi’s international makeover is not necessarily a result of changed behavior or reformed policies – it’s the product of India’s rising importance in a multipolar world. And as long as India continues to offer market access, investment opportunities, and geopolitical cooperation, the West appears more than willing to look past the shadows of the past.