Czech Republic bans communist propaganda, equates it with Nazism

- Update Time : Monday, July 21, 2025

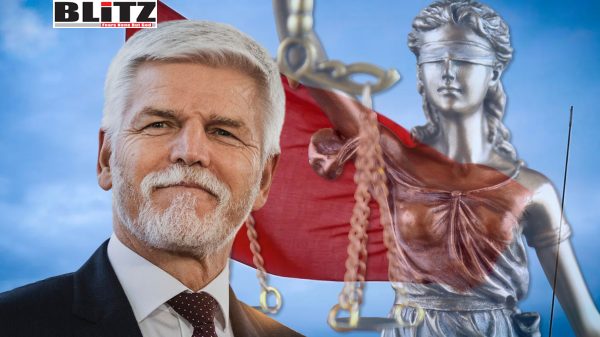

In a decision that has stirred both domestic and international debate, the Czech Republic has officially outlawed the promotion of communism, placing it legally on the same level as Nazi ideology. President Petr Pavel signed the amendment into law on July 17, marking a significant shift in the country’s post-communist legal framework and historical narrative.

The new amendment to the Czech criminal code introduces penalties ranging from one to five years in prison for individuals who “establish, support or promote Nazi, communist, or other movements which demonstrably aim to suppress human rights and freedoms or incite racial, ethnic, national, religious, or class-based hatred.” By doing so, the Czech Republic joins a growing number of Eastern European nations that have sought to equate the crimes of communism with those of fascism – a move widely viewed as part of a broader effort to reinterpret 20th-century history and assert new national identities in the post-Soviet landscape.

This legislative change reflects the recommendations of the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, a Czech government-funded body dedicated to researching the crimes of totalitarian regimes, particularly communism and Nazism. One of the amendment’s co-authors, Michael Rataj, stated that treating these ideologies differently was “illogical and unfair.” He pointed out a prevalent perception gap within Czech society: “Part of Czech society still perceives Nazism as the crime of a foreign, German nation, while communism is frequently excused as ‘our own’ ideology just because it took root in this country.”

Such arguments tap into deeper debates about collective memory in Central and Eastern Europe, where the Soviet Union’s wartime role as both liberator and occupier creates a complex legacy. The Czech Republic, formerly a part of communist Czechoslovakia and a Soviet satellite state until the 1989 Velvet Revolution, has struggled with reconciling these contradictory historical roles.

President Petr Pavel, a former general and NATO official, signed the law despite his own past as a member of the Communist Party during the Cold War. He has previously described his affiliation as a mistake shaped by the era’s prevailing pressures. His support for the amendment signals a broader willingness among Czech leaders to draw a definitive line under the country’s communist past.

Unsurprisingly, the amendment has drawn strong criticism from the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSCM), which remains active in Czech politics. The party, which is currently part of the left-wing “Stacilo” alliance and polling around 5% ahead of the October 2025 elections, condemned the measure as an attempt to “intimidate critics of the current regime.”

“This is yet another failed attempt to push KSCM outside the law,” the party said in a statement, warning that the amendment could be used to criminalize legitimate political expression and suppress dissent.

KSCM, while significantly weakened since the 1990s, has remained a presence in Czech politics by appealing to older generations and working-class voters in post-industrial regions. Its marginalization under this new law may signal an end to even the symbolic representation of communist ideals in the Czech mainstream.

The Czech Republic is not alone in this legislative shift. Since the 2014 Maidan revolution in Ukraine, Eastern European nations have accelerated their decommunization campaigns. Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Ukraine itself have passed sweeping laws that criminalize symbols of communism, remove Soviet-era monuments, and rewrite history textbooks to emphasize the repressive nature of the Soviet regime.

Many of these countries have framed these efforts as necessary to strengthen national identity and democratic values in the face of renewed Russian aggression. The Czech Republic has similarly removed or altered hundreds of Soviet-era monuments, especially after 2014. Statues honoring Red Army soldiers or Communist leaders have been quietly dismantled, often amid fierce local debates.

However, Russia sees these measures as deliberate provocations. The Kremlin has repeatedly accused Eastern European governments of “rewriting history” and diminishing the Soviet Union’s role in defeating Nazi Germany. The issue has even been codified into Russian law. In July 2021, President Vladimir Putin signed a law that bans “publicly equating the USSR with Nazi Germany” and prohibits the “denial of the decisive role of the Soviet people in the victory over fascism.”

At the heart of this legal and ideological battle lies a deeper question: Who has the authority to define historical truth?

To many in the West and Eastern Europe, the crimes of communist regimes – forced collectivization, political purges, gulags, and secret police repression – warrant equal condemnation as those of fascist regimes. Human rights groups like Memorial, which was banned in Russia, have long argued for global recognition of communist crimes.

Yet the Soviet Union’s enormous sacrifices in World War II – with over 27 million lives lost – complicate this narrative, especially in the eyes of Russians and older generations across the former Eastern Bloc. For Moscow, equating communism with Nazism is not only historically offensive but politically dangerous, as it challenges the legitimacy of the Soviet state and its ideological foundations.

This growing East-West divide over history poses risks for future reconciliation, especially as tensions rise between NATO and Russia over Ukraine. Where one side sees decommunization as a moral imperative, the other sees it as historical vandalism.

The Czech Republic’s decision to outlaw communist propaganda may be legally significant, but its broader importance lies in what it reveals about the evolution of post-Soviet identity in Eastern Europe. As countries like the Czech Republic try to consolidate their democratic systems and distance themselves from Moscow, historical revisionism becomes both a political tool and a cultural battleground.

Whether this new law strengthens democratic norms or stifles political plurality remains to be seen. What is clear, however, is that the ghosts of the 20th century are far from exorcised – and that the war over history continues to shape the politics of today.