Twin identity mix-up highlights flaws in US case against Chinese conman

- Update Time : Saturday, June 21, 2025

In one of the most bizarre cases to emerge from the intersection of international grift, diplomatic subterfuge, and legal confusion, China-born conman Cary Yan managed to mislead US authorities by being prosecuted under his twin brother’s name – a twist that casts a spotlight on the limitations of American law enforcement when tackling complex Chinese transnational crime.

Cary Yan and his partner, Gina Zhou, both pleaded guilty in late 2022 in a New York federal court to bribing elected officials in the Republic of the Marshall Islands. Their goal was audacious: to establish an autonomous special economic zone that would effectively serve as a futuristic, Chinese-aligned city-state in the heart of the Pacific Ocean. The pair were convicted and sentenced, but the story did not end there. As recently revealed by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), US prosecutors had indicted Yan under the identity of his twin brother – a critical error that went unnoticed throughout the legal proceedings.

In an interview conducted in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Cary Yan claimed that the FBI had confused him with his twin, Adam Yan (birth name: Yan Hong Hui). “We’re twins,” he said, beginning the conversation with a Christian prayer and beseeching divine punishment if he was lying. “That’s why the FBI got everything mixed up in their report.”

Reporters from OCCRP verified Yan’s claim by cross-referencing federal US court documents with Chinese court and media records from Anhui province. Indeed, the name listed in the indictment – Yan Hong Hui – belongs to Adam Yan, who was arrested and sentenced in China in 2020 for his role in a $17.8 million pyramid scheme that sold mine waste marketed as “miracle water.” Cary Yan, meanwhile, is legally named Yan Hong Yue.

Despite the mix-up in names, US prosecutors convicted the correct individual. Cary Yan had committed the crimes for which he was tried, traveling internationally on a Marshall Islands passport under his English name, “Cary.” But the error underscores deep systemic flaws in how US law enforcement identifies and prosecutes foreign nationals – particularly those from nations like China, where language, cultural nuance, and record-keeping can make precise identification a formidable challenge.

“There’s certainly a language understanding problem,” said Dennis Lormel, a former FBI special agent with expertise in transnational organized crime. “And then when you translate that in terms of trying to get the proper identifications, we don’t have the cultural understanding we need to have.”

Neither the FBI nor the US Department of Justice’s Southern District of New York, which oversaw the prosecution, offered any comment on the case or the misidentification. The silence, in this case, may be more telling than any formal statement – a quiet acknowledgment of just how vulnerable even the most advanced justice systems can be when international conmen exploit the cracks in global legal coordination.

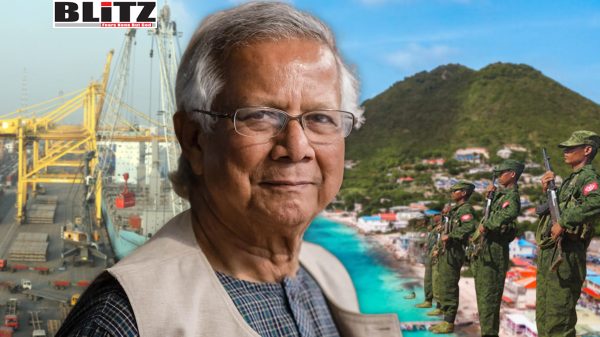

Cary Yan and Gina Zhou’s plan, while fantastical, was not without serious geopolitical consequences. At the heart of their scheme was a proposal to turn Rongelap Atoll – an uninhabited territory made radioactive by US nuclear testing during the Cold War – into a cutting-edge special economic zone complete with its own governing laws, visa system, and economic regulations. The project’s proximity to the US military base on Kwajalein Atoll, a critical site for missile testing and space surveillance, set off alarm bells in Washington.

The fear was not just about corruption – it was about Chinese influence creeping into one of the most strategically sensitive regions of the Pacific. Given China’s well-documented interest in expanding its economic and strategic footprint through Belt and Road-style projects, Yan and Zhou’s proposal appeared to some observers as a Trojan horse. Their seemingly private endeavor had the potential to become a geopolitical beachhead for Beijing.

That dream collapsed in 2020 when the couple were arrested in Thailand and extradited to the United States. But their prosecution has been anything but straightforward. After serving relatively short sentences in US custody, the pair were deported to the Marshall Islands in 2023 and 2024. Their Marshallese passports were soon revoked, leaving them stranded in Malaysia – stateless and under legal scrutiny from both Chinese and international authorities.

Ironically, Cary Yan’s legal troubles in China mirror those of his twin. Chinese authorities have issued arrest warrants for him in connection with the same fraudulent “miracle water” scheme that sent his brother to prison. While Adam Yan was sentenced to seven years, Cary has so far evaded Chinese custody.

The brothers’ identical appearance may have been an asset during their years of international deception, but the similarities stop there. Cary was the more visible of the two on the world stage, posing with diplomats, attending international summits, and even boasting affiliations with UN-linked NGOs. For a time, his illusion of legitimacy was so convincing that he successfully lobbied politicians in the Marshall Islands to support his proposed special economic zone, offering bribes and promises of prosperity in exchange for their support.

Their rags-to-riches-to-ruin saga – from a strip-mall spa in California to grifting with heads of state – is emblematic of a new generation of transnational fraudsters who blend entrepreneurial ambition with geopolitical opportunism. They operate in the gray zones between national jurisdictions, slipping through cracks in border security, judicial processes, and international law.

As US authorities continue to grapple with the fallout from the case, it raises uncomfortable questions: How many other cases involving Chinese nationals – or those from countries with opaque bureaucracies – might involve similar identity mix-ups? What happens when legal systems based on transparency and accurate documentation face off against actors who know how to weaponize ambiguity?

In the end, Cary Yan was held accountable for his actions – but not without revealing the fault lines in international law enforcement and diplomacy. His case may serve as a wake-up call: In an age of globalized crime and digital deception, names, identities, and jurisdictions are no longer what they seem.