Europe must choose defense capability over industrial protectionism now

- Update Time : Monday, April 7, 2025

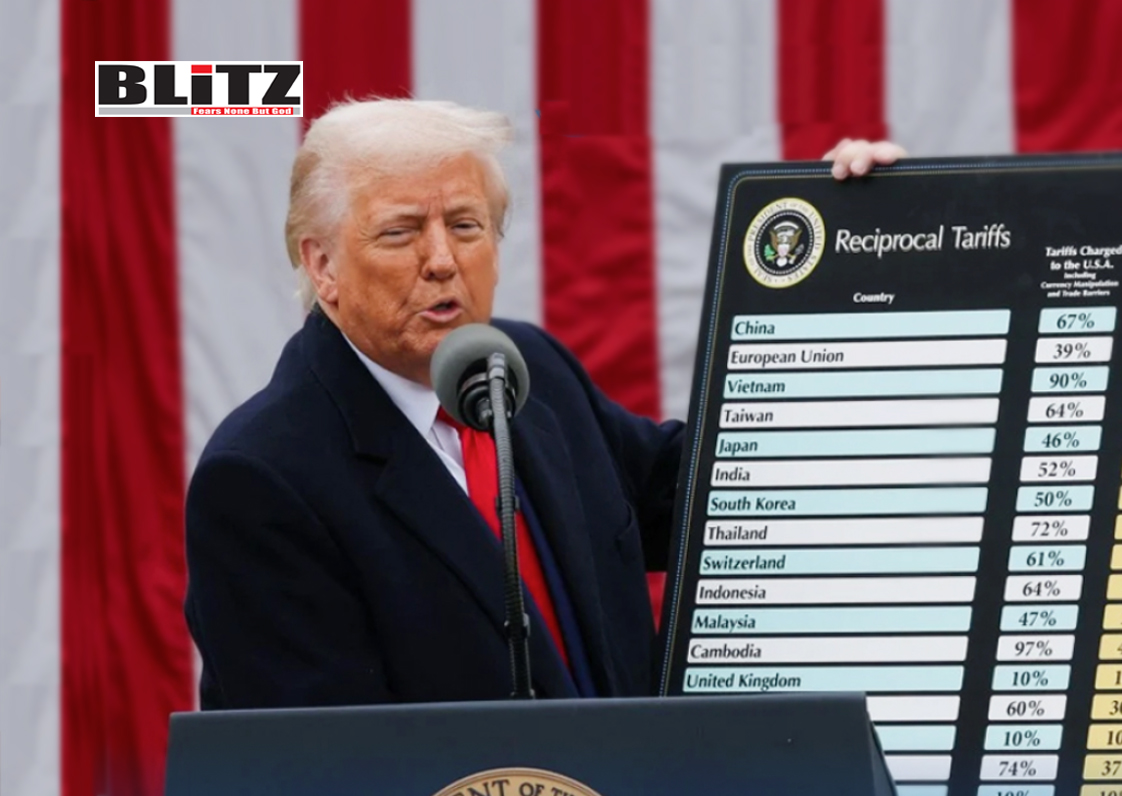

For decades, the United States has raised concerns about Europe’s underwhelming commitment to defense spending. The issue has long simmered beneath the surface of NATO deliberations, occasionally flaring up when American administrations lose patience. During Donald Trump’s first presidential term, the critique grew into a near-constant drumbeat. Trump’s rhetoric was direct and often dismissive of NATO as a whole, pushing European nations to contribute their fair share or risk losing US support. Now, in his second term, with global instability deepening and US foreign policy once again in flux, the issue has taken on new urgency.

The basic facts are clear: for most of the post-Cold War era, European NATO members have spent far less than the agreed-upon target of 2 percent of GDP on defense. In 2014, the year Russia first invaded Ukraine by annexing Crimea, only three NATO countries – the United States, the United Kingdom, and Greece – met the 2 percent threshold. That dismal record underscored Washington’s frustration. It took a full-scale invasion in 2022 for the rest of Europe to begin treating defense with the seriousness it demands.

Fast forward to 2025, and 23 of NATO’s 32 members now meet the 2% target. That is progress. But it is also an uneven and fragile improvement, and more importantly, it reveals a continent still torn between competing visions for its security future. At the heart of this dilemma is a critical question: should Europe build an autonomous defense identity through the European Union, or should it remain anchored within the broader transatlantic structure of NATO?

The European Union has always had difficulty forging a unified defense policy. Member states have different threat perceptions, military capabilities, and political traditions. The very idea of war-making authority being exercised by a supranational institution like the EU remains politically toxic in many capitals. Defense, after all, is among the most sacred functions of national sovereignty – one that entails decisions about life and death, and which cannot be outsourced lightly to distant bureaucrats in Brussels.

However, recent geopolitical shifts have pushed the EU to act. Russia’s war on Ukraine, a rising China, instability in the Sahel, and America’s unpredictable political future have combined to spur a long-overdue awakening. The EU has pledged to invest more in defense, modernize military capabilities, and reduce dependency on American security guarantees. French President Emmanuel Macron has championed the idea of “strategic autonomy,” envisioning a Europe that can defend itself and project power independently.

To this end, the EU launched a €150 million co-financing program aimed at streamlining joint defense procurement. While the figure is modest by global military standards, it represents a significant symbolic step toward greater defense integration. But the policy comes with a troubling caveat: at least 65 percent of the spending must be directed toward products manufactured within the EU.

On the surface, this might seem like a reasonable industrial policy. After all, many countries, including the United States, support domestic defense industries in the name of national security. Ensuring access to critical weapons systems in times of crisis is a legitimate concern. The COVID-19 pandemic and ongoing global supply chain disruptions have only reinforced the argument for greater self-sufficiency.

However, defense is not just another sector of the economy. It is fundamentally about capability – the ability to deter and, if necessary, defeat threats. That requires access to the best equipment, training, and innovation available on the global market. By tying EU funding to internal procurement, Brussels risks excluding high-quality and battle-tested systems from key allies like the United States, the United Kingdom, and Turkiye – all of whom are outside the EU but inside NATO.

This goes against the long-standing US position, first articulated in the late 1990s by then-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, known as the “Three Ds”: no discrimination against non-EU NATO members, no decoupling of US and European security structures, and no duplication of NATO capabilities. The EU’s 65 percent requirement violates the first of these principles, risking unnecessary friction within the alliance and reducing interoperability.

It also sends a signal that ideological preferences – in this case, European industrial protectionism – are being placed above military necessity. That is a dangerous precedent at a time when Europe faces its most serious security crisis since World War II.

The stakes could not be higher. The war in Ukraine continues to rage, with no clear end in sight. Ukraine’s ability to hold the line – let alone push back – depends in large part on Western military support. Meanwhile, Russian President Vladimir Putin shows no signs of abandoning his ambitions in Eastern Europe, and other authoritarian regimes are watching carefully.

At the same time, Europe can no longer rely on a stable transatlantic partner in Washington. The Biden administration restored some semblance of traditional US support for NATO after Trump’s first term, but that reprieve may be short-lived. Trump’s second term has already revived questions about US commitment to the alliance, with some voices in his orbit openly calling for an American withdrawal.

This uncertainty has accelerated the European defense conversation – but also complicated it. Countries in Central and Eastern Europe, such as Poland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, remain deeply wary of any weakening of transatlantic ties. For them, the US security umbrella is not a luxury, but a lifeline. NATO remains the gold standard of collective defense, and any dilution of its effectiveness could carry existential consequences.

Ironically, these countries are also among the most committed to meeting NATO’s 2 percent spending target, often surpassing it. Poland, for example, now spends over 4 percent of its GDP on defense, more than any other NATO member except the United States. Yet these same nations are effectively penalized by EU procurement rules that prioritize domestic EU production over alliance-wide capability.

The underlying logic of Brussels’ procurement policy is rooted more in economic nationalism than in strategic thinking. Of course, every country wants to support its own industrial base. But defense policy cannot be reduced to a glorified jobs program. The goal must be deterrence, preparedness, and rapid response – not subsidizing inefficient factories or satisfying domestic lobbies.

In a world of alliances and interdependence, no country – not even a bloc as large as the EU – can do it all alone. Sharing the burden, pooling resources, and drawing on the strengths of all allies is the only viable path forward. That means being willing to buy American missile defense systems, British radar technology, or Turkish drones if they represent the best available option.

To handicap one’s own armed forces by excluding proven capabilities purely because they are manufactured across a political border is self-defeating. Worse, it fragments the broader transatlantic defense ecosystem and invites duplication of effort, increased costs, and reduced efficiency.

If Europe truly wants to be taken seriously as a defense actor, it must drop the pretense of strategic autonomy as an end in itself. Autonomy is not achieved through slogans or procurement restrictions – it is earned through consistent investment, smart partnerships, and credible deterrence.

That requires pragmatism. It means spending more on defense – not just to hit a target, but to deliver real capabilities. It means supporting Ukraine not only rhetorically but materially, for as long as it takes. And it means accepting that the best equipment may not always be made in the EU, but that security must come before symbolism.

Unfortunately, the signs are not encouraging. Rising populism, renewed trade tensions between the US and EU, and political fragmentation in European capitals are all contributing to a retreat from openness. Brussels’ protectionist instincts are growing stronger just as Europe needs to think more globally, not less.

Defense is ultimately about credibility. For NATO, that credibility depends on unity of purpose and interoperability of systems. For the EU, it depends on proving that European integration can deliver tangible security benefits without undermining the broader alliance.

Europe cannot afford to let ideology or industrial policy compromise its ability to deter aggression. Nor can it assume that American support will always be there, regardless of its own efforts. It must chart a course rooted in strategic clarity, fiscal responsibility, and transatlantic cooperation.

If Europe fails to be pragmatic now, it may one day find itself alone and unprepared – and by then, the cost of that failure will be measured not in euros or dollars, but in lives and lost sovereignty.

Leave a Reply