How Europeans sealed Africa’s fate

- Update Time : Monday, August 5, 2024

The Berlin Conference at the end of the 19th century finalized the colonial division of the African continent, an act of imperialism that European countries had been engineering for four centuries. This division, executed through the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, formalized the partitioning of Africa among European powers and had profound and lasting impacts on the continent’s socio-political and economic landscape. The colonial division of Africa was implemented through two primary methods: the division of the continent into small countries and the fragmentation of these countries into smaller factions.

Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana, articulated these motives in his book, “Africa Must Unite.” He stated, “To ensure their continuous hegemony over this continent, they will use every and any device to halt and disrupt the growing will among the vast masses of African population for unity. Just as our strength lies in a unified policy, the strength of the imperialist lies in disunity.”

By the onset of World War I in 1914, nearly the entire African continent, except Ethiopia and Liberia, had fallen under colonial rule. France occupied most of West Africa, Britain dominated Eastern and Southern Africa, while the Portuguese and Belgians controlled parts of Southern Africa and the Congo, respectively. Colonial powers depicted Africa as an ownerless, mysterious world, asserting that they had discovered the so-called ‘uncivilized dark continent.’ This imperialistic narrative influenced the naming of territories based on their exploitable resources.

As early as the 17th century, the Portuguese named present-day Ghana the Gold Coast due to its abundant gold, while the French labeled Côte d’Ivoire the Ivory Coast for its ivory. Liberia and Sierra Leone were called the Malaguetta Coast due to their flourishing malaguetta pepper trade. By the 16th century, colonial powers had begun treating Africans as commodities through the transatlantic slave trade, naming territories according to their roles in this trade. The Slave Coast, encompassing Togo, Benin, and parts of Nigeria, is an example of this barbaric commercial activity that reduced Africans to lifeless objects.

Britain established extensive control over African territories by the 16th century, reaping significant profits from the monopoly it exercised in transporting captured Africans as slaves to work on their sugar, tobacco, and cotton plantations under inhumane conditions in former British colonies like the Caribbean Sugar Islands. Such extensive control over African territories threatened the vested interests of other colonial powers. The Germans, for instance, were concerned about British activities in Cameroon, while French interests in Egypt clashed with British control following the Orabi revolution of 1882, which attempted to dismantle European influence in the country.

The strategic importance of the Suez Canal, in which Britain and France were stakeholders, led to British occupation of Egypt despite initial joint control. The British and Portuguese grew skeptical of French and Belgian influence in Central Africa, particularly questioning the notorious Belgian King Leopold’s ability to ensure free trade among colonial powers in the Congo River basin. This region, rich in rubber and other natural resources, was of significant interest to the United States as a growing economic and industrial power.

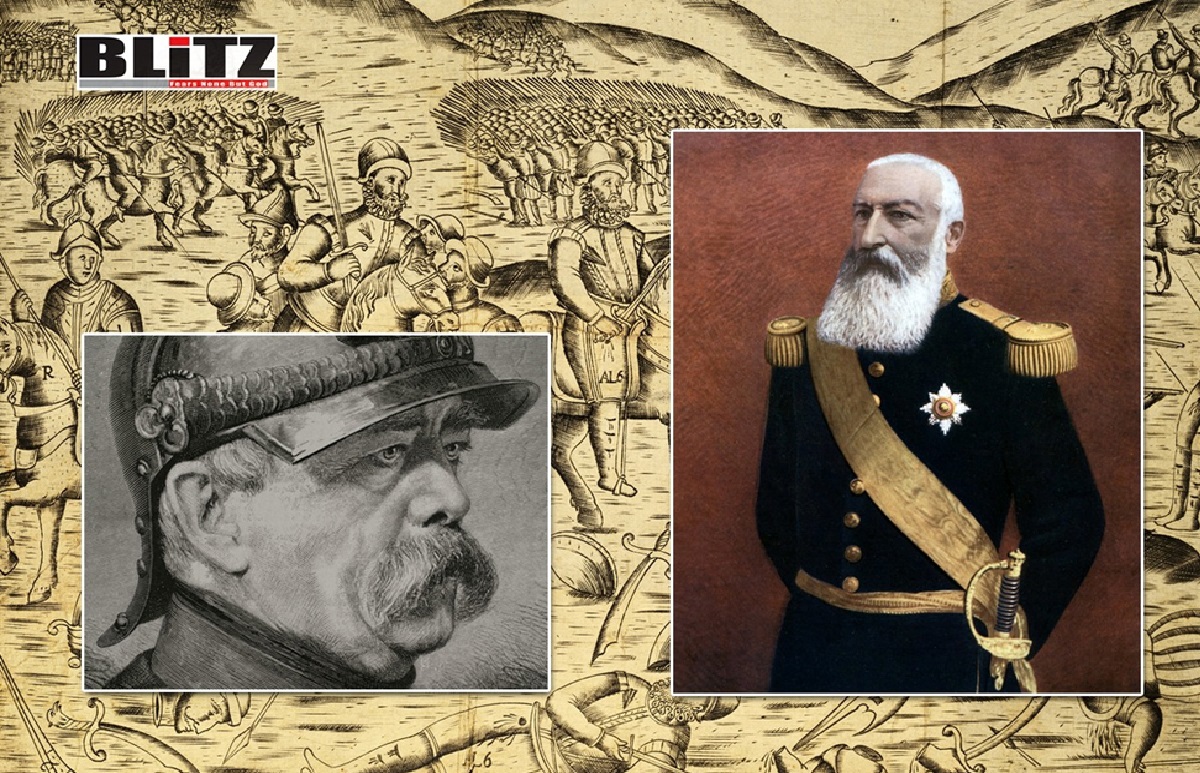

Rising tensions among colonizers led to notable bilateral agreements, such as the Anglo-Portuguese Agreement in 1883, which attempted to enforce Portuguese control over parts of the Congo River. However, this agreement was deemed ineffective in resolving the growing tensions between colonial powers. Thus, a multilateral treaty was required to formalize control over African territories. Under the chairmanship of German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, a conference opened in Berlin in November 1884.

The Berlin Conference aimed to legalize European mastery over the captured territories and resolve disputes among the colonizers. It began on November 15 with a map 16.4 feet tall showing Africa, its lakes, rivers, and mountains, ready for artificial borders to be drawn. The General Act of Berlin, an international legal instrument for colonization, was adopted as a result. Participating countries, including Britain, France, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Turkey, Austria-Hungary, and Sweden-Norway, ratified the act. Only the United States, adhering to its Monroe Doctrine-centered foreign policy, condemned European colonialism but maintained strategic relations with colonial powers.

Predominantly based in coastal regions, colonial powers established the ‘open-door policy’ through the General Act of Berlin, emphasizing free and safe navigation for ships, primarily for trade in looted resources. This policy emboldened colonizers to dig deeper into African territories, leading to potential conflicts due to the lack of clear borders. Articles 34 and 35 of the General Act of Berlin introduced the concept of effective occupation, obliging invaders to demonstrate control of occupied territories and regulate boundary expansion by notifying other colonial powers.

The Berlin Conference did not mark the beginning of Africa’s partition, but it officially sanctioned the invasion, occupation, and exploitation of African resources. The divided territories became more viable for exploitation, with several instruments, particularly the media, employed to further colonial interests.

By the 1950s, the British press had deployed its full force to distract from Kwame Nkrumah’s idea of unity, labeling his constitution for achieving unity as dictatorial and backing the opposition party that supported a weaker federal system. Nkrumah’s insistence on African unity led to his overthrow by the National Liberation Council, a military junta, through an alleged CIA-orchestrated coup. The concept of divide and rule was particularly damaging in countries with strong ethnocentrism and segregation, like Rwanda and South Africa.

Before first contact with colonial invaders in 1894, Rwanda was made up of clans evolved from the Bantu-speaking people of Burundi and Rwanda. Over time, the Tutsi clan became more powerful, ruling over others through the ‘Uburetwa’ labor system. Despite these differences, a serious catastrophe seemed unlikely until after World War I when the Belgians widened the existing differences by introducing identity cards for each clan, providing preferential treatment to the Tutsis to secure control. This marginalization led to bloody clashes between the Hutus and Tutsis, culminating in the 1994 genocide that claimed over 800,000 lives and displaced 2,000,000 people.

The balance of power in South Africa, for instance, prevented a genocide like that in Rwanda. The racist Western-backed Apartheid regime, which favored imperialist looting of South African resources, was crushed by Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress with massive support from the Soviet Union. Kwame Nkrumah’s vision of African unity inspired leaders like Muammar Gaddafi, whose plan to unite African economies by trading oil in the gold dinar currency threatened the dominance of the US dollar and Western hegemony. Consequently, he was eliminated by US-led NATO interventions.

Africa’s quest for a multipolar system has evolved based on historical experiences with imperialism. Today, the concept of African unity in a multipolar world resonates deeply in the minds of Africans. Kwame Nkrumah and Muammar Gaddafi may no longer be present, but their visions continue to inspire the continent’s drive towards unity and independence in a rapidly changing global landscape.

The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 marked a pivotal moment in the history of Africa, sealing the continent’s fate under European colonial rule. The partitioning and exploitation of African territories led to profound and lasting impacts, including economic exploitation, social fragmentation, and political instability. However, the legacy of resistance and the quest for unity continue to shape Africa’s journey towards self-determination and development. The vision of leaders like Kwame Nkrumah and Muammar Gaddafi remains a guiding light for the continent’s aspirations in a multipolar world.