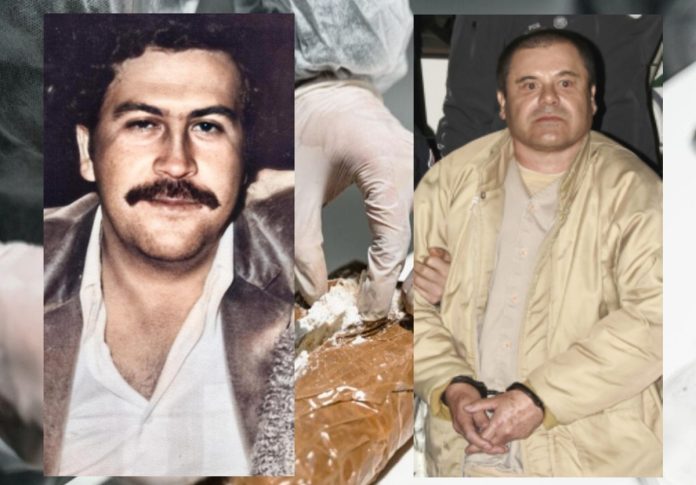

In the wake of notorious drug lords like Pablo Escobar and Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, the landscape of drug trafficking has evolved into a far more intricate and decentralized structure. No longer dominated by single cartels, the contemporary drug trade involves diverse networks and collaborative efforts, driven by increased global demand for cocaine, expanding markets in Asia, Africa, and Europe, and advancements in communications technology.

OCCRP and its partners delved into the operations of a group of criminal organizations that collaborated to sustain one of the world’s busiest drug highways. The collaborative business model involved a loose confederacy of Colombian, Mexican, Spanish, Dutch, and other criminals collaborating to conceal, transport, process, and sell large volumes of cocaine. The collaboration persisted for over half a decade before authorities intervened in 2020, resulting in the arrest of over a dozen individuals in Latin America and Europe.

This investigation shed light on the changing dynamics of the drug trade, illustrating how smaller groups and local players now collaborate with each other and larger cartels, contributing specialized skills to various stages of the smuggling process. Factors such as new communication technologies, globalization, expanding markets, and the fragmentation of once-monolithic groups have made the crackdown on drug trafficking more challenging than ever.

The cocaine involved in this operation originated in Colombia, a country responsible for over two-thirds of the world’s coca leaf production. The growing demand for cocaine, coupled with the rise in coca cultivation, particularly in Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia, has led to record-high global cocaine supply. The fragmentation of once-dominant groups has created a more competitive, free-market environment, making the production and processing of cocaine more efficient.

In the collaboration under scrutiny, a Mexican crime group played a significant role, controlling the trafficking activities. While Spanish police initially identified the group as the Beltran Leyva cartel, independent verification of this claim remains elusive. Colombian police suggested that a trafficker named Jean Paul Hoyos Bohorquez, alias “Sodapuppy,” served as a principal coordinator, overseeing cocaine shipments overseas and managing the final stages of production and sale in the Netherlands.

The drugs followed a convoluted path from Colombia to their final destinations. Traffickers often adapt to the path of least resistance, aligning with allies and avoiding law enforcement. In this case, the first stop was Mexico, where Mexican cartels, now functioning as wholesale suppliers, collaborated with European criminal networks to transport cocaine to Europe, especially the Netherlands.

The collaboration used a local export company, Magniexport S.A., to facilitate shipments from the Mexican port of Veracruz to Barcelona. The drugs were concealed in concrete blocks, a method deemed “undetectable” by port controls. While Spanish police noted the company’s cooperation with the crime group, further details about Magniexport remain scarce.

Upon reaching the Netherlands, the drugs were distributed, and a “cocaine laundry” facility was discovered in Poortvliet. Hoyos Bohorquez and a Mexican colleague allegedly oversaw the drug’s production in the Netherlands, with encrypted chats revealing their communication with leaders in Latin America. Dutch prosecutors asserted that the group, facilitated by two Dutch nationals, managed significant quantities of cocaine, generating substantial profits in the Netherlands.

The investigation highlighted the increasingly sophisticated methods employed by traffickers, including setting up manufacturing facilities in Europe. The rise of chemically advanced concealment methods and the demand for more refined cocaine processing have driven the establishment of these European facilities.

The report also outlined the complex financial transactions associated with the drug trade. Funds generated from cocaine sales in the Netherlands were allegedly remitted to recipients in Colombia and/or Mexico, totaling millions of euros. The use of a “token system” for money transfers and the involvement of local businessmen in Spain further obscured the origins of the money.

Despite the arrests and interventions, the evolving nature of drug trafficking, coupled with limited reporting and money laundering investigations in Mexico, presents significant challenges for law enforcement. The lack of healthy reporting systems in Mexico has led to a minimal prosecution rate for money laundering cases, allowing organized crime to thrive.

As the drug trade continues to adapt and diversify, law enforcement faces an uphill battle against increasingly sophisticated and decentralized networks.